- Wolfe Monument – 1832

- Wolfe Well

- Des Braves Monument – translation (1854) and inauguration (1858)

- Cross of Sacrifice – 1924

- Joan of Arc Monument – 1938

- Garneau Monument – 1957

- Centennial Fountain – 1967

- Sundial – 1987

- Monument to the Combatants – 2009

- Lévis and Murray Monuments – 2010

- Commemorative plaques and interpretive panels

- Horseracing

- Cricket

- Lacrosse

- Golf - 1874-1915

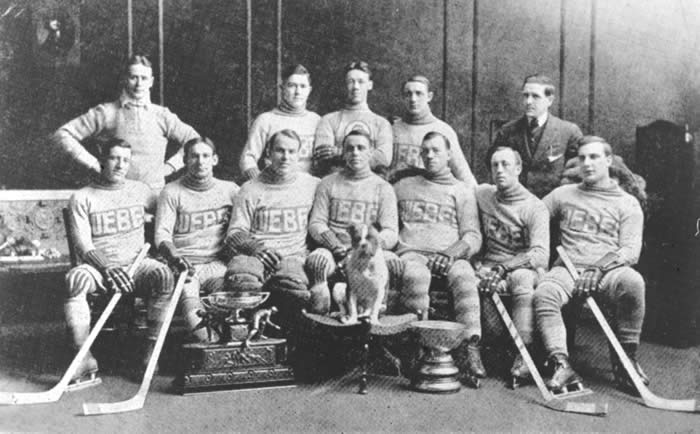

- Ice Hockey

- Ski jumping

- Tennis

- Cross-country skiing

- Snowshoeing

- Tobogganing

- In-line skating

- Agricultural fairs

- Military reviews and manœuvres

- Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day

- Canada Day

- Buffalo Bill – 1897

- Charles Lindbergh – 1928

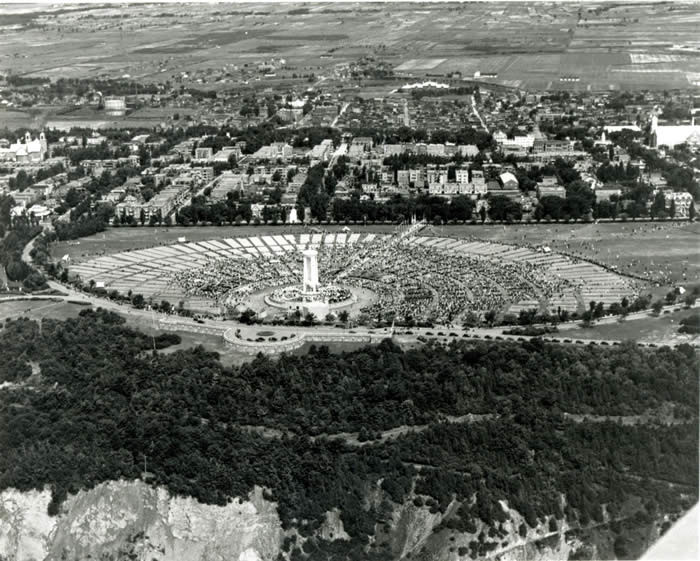

- Eucharistic Congress – 1938

- Superfrancofête – 1974

- Chant’Août – 1975

- Quebec City's tricentennial celebrations - 1908

A Place of Memorial

Wolfe Monument – 1832

The oldest commemorative object on the Plains is the Wolfe Monument, situated in front of the main entrance of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, on the spot traditionally said to be the place where James Wolfe died in the battle of September 13, 1759. Today the monument consists of a Doric column 11.5 metres high surmounted by a helmet and sword. Commemorative plaques on the four sides of the pedestal’s base recall the event and the history of this place of memorial.

The first monument here was apparently a stone rolled by devoted soldiers to the place where Wolfe expired. A benchmark was placed there in 1790 by Major Samuel Holland, the provincial surveyor general. These low-key commemorations answered to the British desire to not yet “honour in such explicit fashion the memory of Wolfe for fear of offending the sensibilities of the people for whom the events of 1759-1760 were still painfully remembered.”

The first monument to Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham. In the background, the cavalry performs exercises.

Credit: H. Church, 1838, LAC.

Some of the English deplored what they felt was a lack of respect on the part of their compatriots toward the victorious general. Prior to 1827, the only memorial to Wolfe was a small statue on the corner of Saint-Jean and du Palais streets. An obelisk was subsequently erected in the Governor’s Garden by Governor Lord Dalhousie. Contrary to customary practice, the monument paid tribute to both fallen generals, Wolfe and Montcalm, in an effort to improve relations between French and English Canadians. However, this gesture was not enough to appease the desire among the English to commemorate one whom they felt was a hero of the Empire.

In 1832, Lord Matthew Whitworth Aylmer, the Governor General of British North America, attempted to rectify the problem by replacing the deteriorated marker on the spot where Wolfe died on the Plains with a real monument, a truncated column with the inscription, “Here died Wolfe victorious - September XIII – MDCCLIX.” Erected at the height of the nationalist movement, just a few years before the revolt of the Patriotes, the monument acquired tremendous symbolic significance.

The power of this symbol would eventually be the cause of its premature demise. It was common practice among visitors of the day to take a piece of the column for a souvenir. Such was its deterioration that by 1849 the monument had to go. In its place was erected a Doric column surmounted by a helmet and sword, a gift from the British army posted in Quebec City. The plaque from 1832 was retained and a second one installed along with it. This time, an iron fence with points was built around the monument to protect it from souvenir-hunting visitors. After more than a half-century of weathering, the monument was replaced in 1913. The National Battlefields Commission ordered a granite reproduction of the column, but kept the plaques and head pieces. A third plaque, describing the history of the preceding monuments, was added.

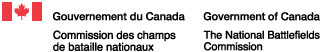

The Wolfe monument on the Plains of Abraham in 1880; in the background, the prison.

Credit: L’Opinion publique, June 10, 1880.

The symbolic value of the site was reaffirmed with the rise of Quebec nationalism in the tumult of the 1960s. For many French-Canadians, the Wolfe Monument was erected to commemorate the defeat of the French Canadian people and stood as “both a symbol of its relegation to the role of a perpetual minority and an affront to its dignity.” [translation] On the night of March 29, 1963, the monument was overturned and destroyed in a gesture ushering in a new extremist group, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). On Victoria Day, May 24, 1965, when thousands of rioters were massed in Montreal’s Lafontaine Park, the base of the Wolfe Monument was defaced with paint.

The re-erection of the Wolfe Monument, deferred until 1965, involved the National Battlefields Commission in the political and linguistic debate in spite of itself. Prior to 1963, the commemorative plaques on its base were written in English only. They were stolen a few months after the demolition of the monument. When a fifth monument was erected in July 1965, it came with new bilingual plaques, in the same year in which the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission) submitted its preliminary report. The new plaques omitted the word “Victorious” after “Here Died Wolfe,” “because some groups of citizens were touchy about it.” [translation] The omission raised a controversy in the Anglophone community, where it was felt that Wolfe had been deprived of his victory. The accusation of softness on the part of the government echoed in the precincts of the House of Commons itself.

The controversies surrounding the history of the Wolfe Monument bear witness to its symbolic importance. More than a place of memorial, the monument is a place of both reconciliation and confrontation where, depending on the spirit of the times, the conflict or harmony existing between the heirs of the two armies who fought on the Plains is expressed.

Illustration: (Canadian Illustrated News, June 5, 1880, p. 365.) See file Canadian_Illustrated_News_ June 5, 1880 _BANQ_p365

Wolfe Well

A few steps away from the Wolfe monument is a well in which water is said to have been drawn to succour the dying general. Since the property on which the well is located has changed hands a number of times since the 1759 battle, the well was filled in and cleared out more than once in the 19th century. It was restored in 1932 by the Dominican brothers and was given in 1942 to the National Battlefields Commission, which has since maintained it.

Wolfe’s well restaured in 1932. Since 1759, the well has been filled in and off many times, which means that the original shape of the well that provided water to the famous general is unknown today.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Des Braves Monument

In the early 1850s, some workers discovered bones that appeared to belong to the soldiers who died on April 28, 1760, in the Battle of Sainte-Foy. On June 5, 1854, the Saint-Jean Baptiste Society undertook to transfer the remains to a common grave on a property donated by a private citizen. To commemorate this French victory, plans were made to erect a monument on the site of the Dumont Mill, where the fiercest fighting had taken place. The cornerstone of the monument was laid on July 18 of the same year, in the presence of a procession of thousands. Also participating in the ceremony was the crew of the French warship “La Capricieuse,” one of the first French ships to visit Quebec City since the Conquest. This symbolic reconciliation coincided with the new alliance between England and France during the Crimean War (1853-1856).

A subscription campaign was conducted by the Saint-Jean Baptiste Society of Quebec to produce the monument designed by architect Charles Baillairgé and constructed by John Ritchie and Joseph Larose. A stone base was erected in 1860, on the occasion of the battle’s centennial. The pedestal and cast column were added on June 24, 1861. The statue on top of the column, a representation of Bellona, the Roman goddess of war, was donated by the French prince Jerome-Napoleon, the cousin of Emperor Napoleon III. The figure stands three metres high, carries a lance and shield, and looks over the part of the battlefield that was occupied by the French army. On the cenotaph furnishing the base of the statue are four bronze mortars. Inscribed on two plaques are the names of Lévis and Murray, the generals who led the opposing armies. The 22-metre monument was officially inaugurated on October 19, 1863.

The Saint-Jean Baptiste Society having run out of money to take care of the statue, the site became the property of the Government of Canada in 1864. The monument was restored, the column was repainted and the base was solidified in 1892; also, the area around the monument was developed. After the creation of the Battlefields Park, the monument and the land became the property of the National Battlefields Commission, which restored the monument in 1914. Des Braves Avenue was developed according to Frederick G. Todd’s plans in 1912. Des Braves Park was built in 1913-1915. The monument was moved a few metres to the north when Chemin Sainte-Foy was broadened in 1970. The rebuilding and restoration work was completed in 2000.

Des Braves Avenue and Des Braves Monument.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Cross of Sacrifice – 1924

Monuments in memory of soldiers fallen in battle were erected in many cities and towns after World War I. Crosses of Sacrifice became a tradition throughout the Commonwealth beginning in the 1920s. On Dominion Day, July 1, 1924, a Cross of Sacrifice was inaugurated at the main entrance to the Plains of Abraham using funds collected by a committee from the people of Quebec City in the area around the Grande Allée. This monument was designed to pay tribute to some 60,000 Canadians, 219 of them Quebecers, who died in the Great War. It reads, “À nos morts de la grande guerre/ To the citizens of Quebec who fell in the Great War.” Je me souviens, the motto of Québec inscribed on the base, evokes the memory of the fallen soldiers. The cross is carved as a monolith and has a bronze sword standing in front of it.

The Croix du Sacrifice, a tribute to Canadian soldiers who gave their lives during the wars of the twentieth century.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

The monument was inaugurated with the Royal 22nd Regiment, the crew of the HMS Valerian and more than 200 veterans in attendance. With many other dignitaries present, including Quebec Lieutenant Governor Narcisse Pérodeau, the cross was unveiled by Canada’s Governor General, Julian Byng, Baron of Vimy. A two-minute silence was observed and flowers were placed at the foot of the monument. A ceremony was held in the fall of 1947 to include in the tribute those who fell in World War II. On November 9, a token quantity of French soil was buried under the knoll on which the cross stands, on the side facing the Grande Allée. Finally, the sacrifice of those who fell in the Korean War (1950-1953) was also commemorated. Every year, at 11 a.m. on Remembrance Day, November 11, the anniversary of the Armistice, a ceremony takes place around the cross, attended by war amputees, veterans, dignitaries and soldiers paying tribute to the soldiers who sacrificed their lives.

Joan of Arc Monument – 1938

This statue of Joan of Arc, seated on a horse and wearing battle garb, rests on a cenotaph made up of a 28-ton block of stone from the Notre Dame mountain range in the United States. Carved by Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973), the statue is apparently one of five reproductions of a work originally commissioned by New York City and standing in Riverside Park since 1915. Other replicas are found in Blois, France, Gloucester, Massachusetts and San Francisco, California.

The story of this monument on the Plains begins with a gift made to the National Battlefields Commission. Captivated by the charm of Quebec City, an American couple, Anna Hyatt Huntington (the sculptor herself) and her husband, who wished to remain anonymous, donated the Joan of Arc Statue. The unveiling of the statute in 1938 caused somewhat of a stir, as a statue dedicated to a saint celebrated for liberating France from the English could hardly play a part in a celebration of good relations between English and French Canadians. However, whatever offence might have arisen from the presence of Joan of Arc in the Battlefields Park was mitigated by the dedication on the monument:

«Comme emblème du patriotisme et de la vaillance des héros de 1759-1760» [A tribute to the patriotism and courage of the heroes of 1759-1760]

The monument and the gardens surrounding it were inaugurated on September 1, 1938.

Joan of Arc Monument in the garden.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Garneau Monument – 1957

Situated in the heart of the Plains at the corner of George VI and Garneau avenues, the Sir George Garneau Monument pays tribute to the Quebec City mayor (1906-1910) who was one of the main authors of the Quebec City tricentennial celebration and of the creation of Battlefields Park. A bronze bust representing him also commemorates his work as Chair of the National Battlefields Commission from 1908 to 1939.

The bust was unveiled on September 7, 1958, by the National Battlefields Commission as part of its 50th anniversary. It was created by Quebec sculptor Raoul Hunter, better known as the caricaturist of Le Soleil newspaper from 1956 to 1989.

The monument to Sir George Garneau and a stone laid in honour of an officer struck down on the battlefield of September 13, 1759.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Centennial Fountain – 1967

To commemorate the centennial of Canadian Confederation in 1967, the National Battlefields Commission erected a fountain on the land formerly occupied by the Quebec City Observatory (1864-1936). The fountain was inaugurated in October 1967. It has two basins, one measuring twelve metres in diameter, with seven waterspouts shooting as high as nine metres in the air. In 2017, the fountain is restored and lighted to highlight the 150th anniversary of Confederation.

The Centennial Fountain.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Sundial – 1987

A sundial was installed by the National Battlefields Commission in the summer of 1987, close to the Centennial Fountain and the existing service building. The sundial, which rests on a block of pink granite, was designed by surveyor Rafael N. Sanchez, then Dean of the Engineering faculty at Tucuman University in Argentina, and professor at Laval University.

This sundial is one of the few that indicates Eastern Daylight Saving Time and is accurate to within one minute. As opposed to the setup of the traditional metal gnomon, the shadow on this sundial is cast by a prismatic aluminum double-crested style. The elliptical face has 1,000 points corresponding to every 10 minutes of the first and fifteenth day of the month from May to October; computer calculations were used in creating it. There is a different coloured line for each month; the intersection of the shadow and the line indicates the time

The sundial is reminiscent of the time in the history of the Plains when the Quebec Observatory and the astronomical work done in it was used to tell time in the city.

The sundial.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Monument to the Combatants – 2009

On September 13, 2009, the National Battlefields Commission unveiled a brand new memorial dedicated to the military and civilian combatants who participated in the battles of 1759 and 1760. 75 or so descendants were present on the actual site of the confrontation to honour the memory of their ancestors, on this historic day of the 250th anniversary of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

The memorial is dedicated to all the civilian and military men who fought in the battles of 1759 and 1760. It is also a tribute to the courage shown by the civilian population of Québec City and its surroundings, who endured the trials of this war and who fought with determination for the survival of their colony.

Designed by Claire Lemieux and Jean Miller, the memorial is made up of three interpretation panels. Built in the form of a three-sided stela, the monument “In honour of the soldiers' recalls the three events the combatants lived through: the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), generally considered as the first world-wide conflict in history, which includes the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (September 13, 1759) and the Battle of Sainte-Foy (April 28, 1760).

In order to respect the sobriety and continuity of the park’s monuments, grey and black granite was chosen and the copper tip is in harmony with the signs posted in the park. At the top of the stela sits an engraved aluminium parchment that symbolizes a page of our history and adds a contemporary touch.

Ceremony - unveiling.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

As for the interpretation panels, they essentially put in context the Seven Years’ War in America and in Québec, as well as a chronology of the main events. The two other panels are devoted to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Battle of Sainte-Foy respectively; each showing the context in which these confrontations occurred, the opposing armies, the battle lines, and the sequence of the battles.

Lévis and Murray Monuments – 2010

On April 28, 2010, on the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Sainte-Foy, the National Battlefields Commission unveiled two monuments celebrating the memory of the French and British troop commanders and of their respective allies. A short ceremony was held at Des Braves Park, site of the confrontation.

Michel Binette, the sculptor, created two finely chiselled bronze works complementing each other, which are worthy representations of generals Lévis and Murray. The sculptures are laid on granite pedestals and bear an inscription paying tribute to the generals who led the French and British troops. Nearby, an interpretation panel evokes the Battle of Sainte-Foy, Des Braves Monument, and the park that bears the same name.

François-Gaston, chevalier de Lévis, and James Murray.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Commemorative plaques and interpretive panels

The National Battlefields Commission uses large monuments to commemorate major battles and important events on the Plains of Abraham. The possibility of enhancing the commemorative function by placing a series of plaques in the park was discussed as early as 1914, but nothing was actually done until 1939, when it was decided to commemorate the King’s first visit to Canada and other historic events related to the Plains of Abraham. During the summer of 1940, 18 commemorative plaques were installed on the territory managed by the Commission.

In addition to commemorating, these plaques are also used to tell stories, explain and introduce certain aspects of the Plains to visitors. Interpretive panels are found throughout the park and pertain to various topics including the Battle of 1759, the astronomical observatory, the golf course, and so on.

Jean Provencher, “The Park of Memories” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 262.

National Battelfields Park, Master Plan: Phase 1 Preliminary Inventory, Ottawa, National Battlefields Commission, 1975, p. 21.

Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ), Inventaires de lieux de mémoire en Nouvelle-France, [http://inventairenf.cieq.ulaval.ca/inventaire/rechercheSimpleForm.do], (November 26, 2007).

Juliette Dutour, “Négociation et Construction Patrimoniales d’une Capitale au 20ème siècle,” Equinoxes, No. 5, (Spring/Summer 2005), par. 9.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900.” In Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 141.

National Battlefields Commission Archives, Minutes of Board of Directors Meeting, April 16 and November 18, 1912.

Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ), op. cit.

Jacques Lemieux, “Wolfe devra mourir une autre fois,” Garnier, May-June, 1963.

Jos.-L. Hardy, “Des actes de vandalisme marquent la fête de la Reine,” Le Soleil, May 24, 1965. p. 8.

Jean-Guy Langlois, NBC spokesman, quoted in “On a enlevé à Wolfe sa dernière victoire,” La Presse, July 27, 1965.

National Battlefields Commission Archives, [Quebec, August 19, 1940], NBC 8400-2/1, vol. 2.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900.” In Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 142.

Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ), Inventaires de lieux de mémoire en Nouvelle-France, [http://inventairenf.cieq.ulaval.ca/inventaire/rechercheSimpleForm.do], (November 26, 2007).

Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ), Inventaires de lieux de mémoire en Nouvelle-France, [http://inventairenf.cieq.ulaval.ca/inventaire/rechercheSimpleForm.do], (November 26, 2007).

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900.” In Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 142.

G.-E. Marquis, Les monuments commémoratifs de Québec, Québec, L’Éclaireur limitée, 1958, p. 140.

G.-E. Marquis, Les monuments commémoratifs de Québec, p. 141.

New York City Statues, [http://newyorkcitystatues.com/statues-in-the-news/2007/10/4/page-of-the-month-anna-huntington.html], (November 26, 2007).

Claude Tessier, “Un cadran solaire qui donne l’heure avancée de l’Est,” Le Soleil, August 14, 1988, p. B-2.

Jean Provencher, “The Park of Memories” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 270.

A Natural Setting

The Plains of Abraham has long been a natural setting that has fascinated visitors. Even in the 18th century, its plant life was a subject of observation to scientists such as Michel Sarrazin, Jean-François Gaultier and Pehr Kalm. Modern visitors, including tourists and residents of the city, enjoy strolling and admiring the splendours of nature displayed there, and especially the beauty of the Joan of Arc Garden, its carpet bedding, its plant beds and its trees.

The Joan of Arc Garden

The Joan of Arc Garden was not included in the original plans prepared by Frederick G. Todd, the architect-landscaper who laid out the park in 1909. It owes its existence to a gift given by an American couple, Archer Milton Huntington and his wife, Anna Hyatt Huntington, who, captivated by the charm of Quebec City, gave to the National Battlefields Commission a statue of Joan of Arc on horseback sculpted by Mrs. Huntington herself. After much discussion as to where to place the statue or whether the French heroine should even be included in the Battlefields Park, it was decided to create a garden with the statue in its midst.

The job of planning the garden was assigned in 1938 to Louis Perron, the first Quebecer to obtain a degree from a university-level school of landscape architecture. His task was to prepare a plan that would incorporate Todd’s overall layout. Perron’s initial plans included four majestic entrances to the garden and two ponds reflecting the Joan of Arc statue. However, the financial constraints arising from the imminence of World War II meant scaling down the designs, replacing the ponds with rose gardens and the majestic entrances with more modest structures.

The Joan of Arc Garden is the floral masterpiece of the Plains of Abraham. It is rectangular in shape, measuring 165 metres by 43, and is built slightly below ground level, as a sunken garden, combining the French classical style with British-style beds, all surrounded by bushy hedges and flanked by a row of Scotch elms. Two-thirds of its contents are perennials, lending the garden an air of spontaneity and naturalness.

The Joan of Arc Garden.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Carpet bedding

Carpet bedding consists in making raised designs or lettering with plants (Santolinas and Alternanthera), selected primarily for the colour of their foliage and even growth. This rather costly technique requires a good deal of preparation and patient attention to detail.

This art has been practised on the Plains since the 1910s. Today carpet bedding is found at the foot of the Park’s main monuments. The National Battlefields Commission Green Space Services Team has also been working for some years on developing original techniques and presentations, for example by varying the types of plants used.

Floral mosaic set up.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Plant beds

Aside from the Joan of Arc Garden and the carpet bedding, other parts of the Park have also been beautified by the Plains horticulturalists. Mixed English-style plant beds are found along Ontario Street, at the Centennial Fountain, the Sundial and the Cross of Sacrifice. All of the plants in the Joan of Arc Garden and the rest of the Park are grown in the National Battlefields Commission greenhouses, located close to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. The largest was built in 1916-17, making it one of the oldest greenhouses still in use today. Thanks to these greenhouses, it is possible to produce a very wide variety of plants and to make them available at just the right time for planting.

Flower beds.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Arboriculture

The Battlefields Park and the Des Braves Park contain close to 6,000 trees and over 90 species. Of these, more than 4,400 have been numbered, geo-referenced and filed in a computer system. The National Battlefields Commission plants new trees each year to replace those that have died and to maintain age diversity among the population. Silver maple, sugar maple, Scotch elm, Norway maple, American white ash and hawthorn are the most common species. Other more unusual and exotic species include Ginkgo bilboa, Western catalpa, Japanese tree lilac, Constantinople hazel and Amur cork tree.

A Playing Field

Horseracing

A pursuit of English gentlemen originating in the 16th century, horseracing was one of the first sports brought to Quebec City by the British. It was heartily endorsed by the authorities, who saw the essentiality of breeding and raising horses for the troops of the Empire.

One of the first horse races on record took place in 1767 on the “Heights of Abraham” and was organized by the soldiers of the Quebec City garrison. In what is considered to be the first sporting horserace advertised in Canada, the prize of $40 was won by a Captain Prescott riding a mare named “Modesty.”

A few races were held on the Plains by the Quebec Turf Club, founded in 1789, but regular races did not take place until the early 19th century. At that time the race track was situated on the western edge of the Plains, the site of what is today the playing field, in front of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. This field, which was leased to the military by the Ursulines, was one of Canada’s premier race tracks, attracting the best horses from the United States and across Canada. The races were attended by thousands of spectators; unruly behaviour, the result of sporting enthusiasm combined with excessive drinking, was not uncommon.

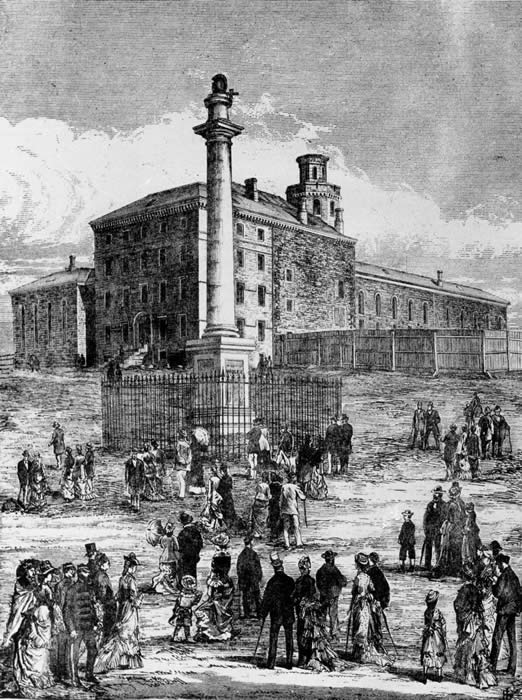

Horses racing on the Plains of Abraham in the ninetheenth century.

Credit: Royal Ontario Museum.

A major competition was held in the summer of 1808, attracting some thousands of spectators, including Governor James Craig. With their sophisticated and complex system of rules, the races were nothing like the more conventional ones held by the Canadians. Since the latter had nothing in their stables that could run with the English thoroughbreds, the Governor, in a gesture of conciliation, put up a purse of 15 guineas to the winner of what would be a race for Canadian horses only. Not many Canadians participated even in this race, since it was to be run in the strictest British tradition, whereas the Canadians generally preferred harness racing. In 1829-1830, the Club organized the Jean-Baptiste Plate, another exclusively Canadian race, with a prize of $20, the monthly wage of a working man.

The Quebec Turf Club organized at least one race day per year until 1830, when growing tension between Anglophones and French-Canadians and the volatile political situation put an end to the practice. Canadian nationalists and the population at large denounced this English gentleman’s sport. Although horseracing continued to be the private preserve of Anglophones, the number of French Canadian participants gradually increased after the 1837-1838 Rebellion and in the second part of the century. In 1847, in an effort to curtail unruly behaviour, the Quebec Turf Club moved the racetrack to l’Ancienne-Lorette, in the hope that the distance would discourage attendance by members of the working class.

Horseracing had become more democratic by the turn of the century and Quebec had four tracks with a variety of programs, including harness racing. With the departure of the British garrison in 1871 and the drop in the city’s Anglophone population, the Quebec Turf Club lost its traditional clientele and discontinued its activities in 1887.

A few events reminiscent of the first horse races on the Plains have since taken place. Buffalo Bill staged his Wild West extravaganza on the racetrack in 1897. The track was also used for the Tricentennial celebration in 1908. Finally, Canada’s best horses were featured at the Quebec City Horse Show in the 1990s and until the early 2000s.

Cricket

England’s national sport was one of the first team sports introduced to Canada. In Quebec City, the first games were played on the Plains in the 1830s. Engaged in primarily by the garrisoned soldiers, cricket is played by two 11-man teams on a large oval field. The teams must be roughly of the same calibre; this made it difficult for the Quebec City garrison to form balanced teams. They often had to await a visit by a British warship to find suitable opponents. Cricket does not seem to have been played regularly. Unlike many other sports brought in by the British, cricket has not taken hold in Canada.

Lacrosse

The British were the first to take an interest in lacrosse, which was adapted from an Amerindian game whose rules they standardized in the mid-19th century. A number of teams were subsequently organized. Not to be outdone, the French-Canadians formed the Champlain Club, their first, in 1868 and played on a field near the Grande Allée, where the Quebec Skating Rank would be constructed. Most of Quebec City’s teams, whether English, Irish or French-Canadian, played their first games on the Plains. Alongside the sporting rivalry was a strong rivalry between nationalities. After a game, the players would retire to a hearty meal at the Fréchette Restaurant on Côte de la Montagne or at the Imperial Hotel.

Major gatherings were the scene of athletic contests (racing, jumping and throwing events) staged on the Plains by the lacrosse players, who would invite other sportsmen to join them. The day would normally end with a banquet and the awarding of prizes at the Skating Rink, always with a large crowd in attendance.

Lacrosse games were played everywhere on the Esplanade, close to the St. Louis gate; if the latter was unavailable, the game took place on the Plains. Since the field was open in every direction, it was difficult for the organizers to make money by charging admission. The Anglophone lacrosse clubs had their own field on Chemin Saint-Louis starting in 1878, which they financed by charging admission.

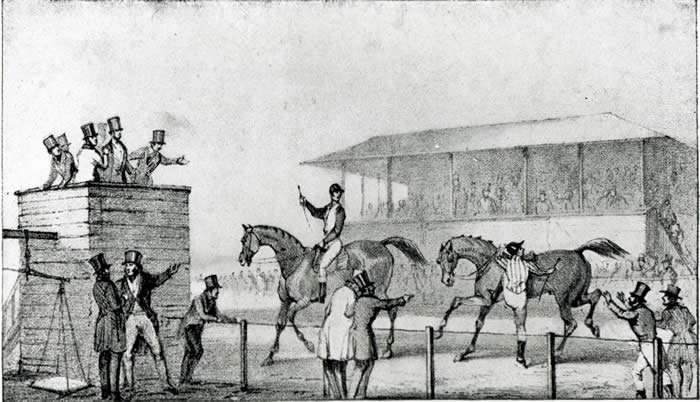

Golf – 1874-1915

The Quebec Golf Club course was founded in 1874, just a year after Royal Montreal, North America’s first club. The Quebec club was created by the British, who built a 14-hole course on the Plains of Abraham at what used to be called the Cove Fields, between the Citadel, the Grande Allée and Martello towers 1 and 2. A farmer’s cows were originally used to cut the grass, a job which was taken over by a horse-drawn mower in the 1880s.

In 1876, in what is reputed to have been North America’s first tournament, the members of the Quebec Golf Club began a tradition of annual tournaments with players from Montreal. As early as the 1880s, the Plains golf course was renowned continent-wide for its historic interest, its incomparable beauty and its fine vistas.

The Interprovincial Cup, emblematic of Canadian golf supremacy, was won by the Quebec Golf Club in 1882, 1887, 1892, 1894 and 1896. It was composed primarily of British players, with the exception of a few French-Canadians, including, in 1899, George Garneau, the Mayor of Quebec City from 1906 to 1910 and first chairman of the National Battlefields Commission. The Club played on the Plains until 1915, moving to Courville (Boischatel) in the 1920s. In 1934, its 60th anniversary, its name was changed to the Royal Quebec Golf Club.

The golf course on the Plains of Abraham between 1874 and 1915.

Credit: Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Ice Hockey

The first records of organized hockey games in Quebec City date back to 1878, with the founding of the Quebec Hockey Club. When constructed in 1877, in front of today’s parliament, the Quebec Skating Rink had no boards or seating for spectators who might wish to watch this new game, with its teams of seven to nine players. The difficulty of finding worthy opponents locally meant that the Quebecers had to challenge Montreal teams. The rules differed from one city to another, and in the first games between themselves and Montreal in the 1880s, the Quebecers deferred to the Montrealers. Starting in 1888, the Quebec team joined the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada and began playing regularly against teams from Montreal, Ottawa, Dartmouth and Halifax.

In the heat of the sometimes intense rivalry, spectators would sometimes join the fray, trying to intimidate the referees, to the point where the Quebec Hockey Club was placed under suspension for a period of time in 1895. Hockey violence was widespread in the late 19th century, to the point where the players “did not hesitate to use their hockey sticks ‘like a butcher would use an axe.’” While this brand of hockey resulted in frequent injuries, it was entertaining enough to attract more than 2, 000 spectators to each game.

In 1889, the Quebec Hockey Club moved into the new Quebec Skating Club arena, situated close to the present site of the Cross of Sacrifice. The team turned professional in 1908 and became known as the Bulldogs. Quebec won the Stanley Cup twice on the Plains of Abraham, in 1911-1912 and 1912-1913. The Plains Skating Club was destroyed by fire in 1918. The Bulldogs joined the National Hockey League in 1917 but played only in 1919, moving to Hamilton in 1920 and changing their name to the Tigers.

Quebec Bulldogs, 1912-1913.

Credit: Unknown.

Unlike cricket, hockey was wildly popular from the early part of the 20th century onward among the French-Canadians, who came to regard it as their national sport.

Ski jumping

Skiing in its various forms was introduced in Quebec in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With its steep slopes and proximity to the city, the Plains of Abraham soon became the choice of the first downhill skiers, both amateur and professional. The Quebec Ski Club began organizing ski jumping competitions on the Plains from the date of its founding in 1907 and helped to promote the sport’s popularity among the people of Quebec City. In March 1909 it held a ski jumping competition on the Cove Fields east of the Citadel, which was won by Harry Scott. Annual competitions were held in the following years. A ski jump was built in 1910 for competitions the winner of which was the contestant who covered the greatest distance in three jumps. The Quebec Ski Club maintained a wooden ski jump behind the buildings of the Ross Rifle Company, close to Martello Tower 1, from 1908 to 1913. The slopes of the Plains were used by downhill skiers into the 1940s and 1950s. Between 1955 and 1980, the Société des cours populaires de ski gave free lessons, including the use of a beginners jump, on the Plains for children 8 to 14.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, ski jumping was practised on the Plains of Abraham. A ski jump was even erected near Martello tower 1.

Credit: LAC, 1918.

Tennis

In 1927 the National Battlefields Commission loaned a field on the site of the former Quebec Skating Rink, close to the Cross of Sacrifice, to the Association des employés civils (the Quebec government employees association). During the 1930s the Association operated tennis courts on the site, which was used as a skating rink in winter. The tennis courts were dismantled in 1937 when the Park entrance was built.

Cross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing was popularized in Quebec City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Norwegians. With its proximity to the city and its magnificent panoramas, the Plains soon came to be regarded as one of the best places around Quebec City for cross-country skiing.

The Commission began discussing the possibility of creating and maintaining cross-country ski trails in the 1980s. Before that time, skiing was pursued at random on the Plains. The project came to fruition in the winter of 1986-1987, with the inauguration of three trails designed by Laurent Fortier and Bill Dobson, well-known figures in Quebec skiing circles. Today the National Battlefields Commission maintains five classical and two skating cross-country ski trails.

Skiers on the Plains of Abraham in 1933.

Credit: W.B. Edwards, Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

Snowshoeing

Snowshoeing originated with the Amerindians and was first used by Canadians as a method of transportation. The British soon gave it a recreational and sporting vocation. In the early 19th century, Anglophone city dwellers and soldiers, especially officers, posted to Quebec City would snowshoe on the Plains in couples or in groups of friends. What started as a method of transportation became a social activity. The Quebec Snowshoe Club, which organized snowshoeing outings and races, many of them on the Plains, was founded in 1845. “This activity was so popular that the editor of Le Canadien suggested, in 1854, that it be made ‘a national Canadian pastime.’” The outings would usually end with a meal in one of the city’s fine restaurants. The Quebec City clubs would sometimes host other associations from Montreal or Ottawa. The Château Frontenac sports committee would also organize skiing and snowshoeing races on courses running through the Cove Fields.

The tradition continues today with the various snowshoeing clubs still in existence in Canada. A snowshoe trail is maintained by the National Battlefields Commission.

Tobogganing

Its steep slopes make the Park an ideal place for tobogganing, another sport that gained popularity in the 19th century. Inspired by an Aboriginal device, a toboggan is a sled made up of a few thin boards whose front ends curve upward. It can hold up to three people, usually seated, although daredevils may stand upright. The city’s elite could be found tobogganing on the Plains on fine winter days. The cozy seating of toboggan riders was condemned by the Catholic clergy. A slide requiring admission fees was built at the turn of the century on the slopes of the Citadel.

Tobogganing on the Plains of Abraham.

Credit: D. Gale, 1860, LAC.

In-line skating

In-line skating, which became the rage in the 1990s, is prohibited on the streets crossing the Plains by the National Battlefields Commission, in compliance with Quebec’s highway safety code. However, in view of this new sport’s growing popularity, the Commission opened a multipurpose track in 1996 on which in-line skating is allowed. The June 22 inauguration featured a skate-a-thon with speed skater and Olympic champion Gaétan Boucher in attendance. The 1.3 km paved track is situated inside the jogging path, in front of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

True to its vocation, the Battlefields Park is still a vast playing field for those who enjoy sports in the Capital. In addition to in-line skating, a number of other sports may be pursued in the park’s hospitable environment by the general public including running, walking, bicycling, football, soccer, cross-country skiing and more.

Jean-Marie Lebel, “Buffalo Bill, des plaines du Far-West aux plaines d’Abraham,” Chroniques historiques, Quebec City: Commission de la capitale nationale, [http://www.capitale.gouv.qc.ca], (May 29, 2002).

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 160.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” p. 159.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” pp. 159-160.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 161.

Noël Baillargeon, Le club de Golf Royal de Québec, 1874-1974, [Québec, Le Club de golf Royal Québec, 1974], p. 23.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” 161-162.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 162.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” p. 163

“Saut pour les skieurs,” Le Soleil, January 5, 1921.

“Quebec Ville boréale! Ville de ski!,” Musée de la civilisation/Musée du ski. [s.l.], [s.n], [s.d.], p. 8.

National Battlefields Commission archives, [correspondence between the NBC and the Association des employés civils], 2650-1/25, vol 1.

Pierre Savard, “Des ‘vrais’ pistes sur les Plaines!” Le Soleil, October 19, 1986.

For further information on services, see http://www.ccbn-nbc.gc.ca/_en/sportsloisirs.php .

Donald Guay,“Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800-1900,” p. 165.

“Les sports demain,” Le Soleil, January 15, 1921.

For further information on services, see http://www.ccbn-nbc.gc.ca/_en/sportsloisirs.php

A Site for Major Events

For a very long time, the Plains of Abraham have been a pre-eminent meeting place. Even before the creation of Battlefields Park in 1908, events such as agricultural fairs were organized as of the end of the 18thcentury. The army also used the Plains in the 19thcentury for military reviews and manoeuvres, which attracted many curious onlookers. At that time, the site also hosted a variety of circus acts, the most famous being that of William Frederic Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill.

During the 20th century, the Plains of Abraham were also witness to some major events, including the very famous Charles Lindbergh’s landing on April 24, 1928. The Eucharistic Congress of 1938 as well as two festivals, the Superfrancofête in 1974 and the Chant’Août in 1975, are a few other events that attracted huge crowds.

The site has also been used to celebrate and commemorate outstanding historical facts. One such commemoration, the Quebec City’s tricentennial celebrations in 1908, was even behind the creation of Battlefields Park. Fifty years later, the City again availed itself of the Plains in organizing its 350th anniversary festivities. The Plains of Abraham also took part to the 400th anniversary celebrations in 2008.

Every year, the Plains also host activities related to popular festivals and celebrations. For example, the Quebec City Summer Festival organizes an array of music concerts there, while the Quebec Winter Carnival uses the park for its snow carving competition and its “family space,” a family play area for activities such as sliding, dogsledding and snow rafting.

Battlefields Park also hosts festivities related to Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day and Canada Day. The first is a very ancient Christian celebration coming from a summer solstice pagan ritual, and has long been celebrated in Europe. In New France, June 24 was also marked by religious ceremonies and took on a political aspect only in the 19thcentury. The Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society of Montreal, a nationalist movement aimed at boosting solidarity among French Canadians, was founded in 1834. A similar Society was later created in Quebec City in 1842. Since that time, June 24 has become the celebration of French Canadians. In Quebec City, among the major events related to Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day was the Great Convention of 1880, which assembled representatives of all Francophone communities in North America. The Plains were at the centre of the event and hosted close to 40,000 people for a mass on the Buttes-à-Nepveu.

After being declared a holiday in 1925, June 24 officially became Quebec’s national holiday in 1977. From that time on, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day would evolve from a celebration for French and Catholic Quebeckers to one for all Quebeckers. Since 1984, Quebec City’s Société nationale des Québécois et des Québécoises de la Capitale has been commissioned to organize Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day festivities, and the Plains of Abraham have proven year after year to be the preferred location and focus for presenting large-scale shows and organizing family activities such as the “Grande Tablée” picnic.

One week after Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, on July 1 it is Celebrate Canada!’s turn to avail itself of the Plains of Abraham to mark Canada Day. Commemorating the entry into force of the Act that established the Dominion of Canada in 1867, July 1 was celebrated sporadically over the first 100 years of the country’s history, before celebrations commemorating Canada’s centennial attracted worldwide attention, partly due to Expo67 in Montreal. The event was indeed a catalyst, because since then “Dominion Day,” renamed “Canada Day” in 1982, has been celebrated more outstandingly and especially more regularly throughout the country; in Quebec City the Plains of Abraham, that pre-eminent meeting place, inevitably plays a key part in the festivities.

Battlefields Park frequently hosts a variety of organizations looking to stage their activities: sporting, fundraising, filming, etc. Some of them are held annually while others are one-time events. One such event was the first snow jam in modern scouting history was held on the Plains from December 27, 1999, to January 5, 2000. During this event, which assembled about 2,600 scouts from all over the world, Battlefields Park once again played its part as a meeting place at the centre of the City.

Agricultural fairs

The Plains of Abraham site is auspicious for gatherings, such as agricultural fairs, which require wide-open spaces. Founded in 1789 by Governor Lord Dorchester, the Quebec Agricultural Society held its first exhibitions on the Plains. During the summers of 1818 and 1819, the site was once again made the centre of such shows at which, over a few days, visitors could admire the region’s handsomest animals, grains and produce, mainly from Anglophone exhibitors. Ploughing contests were organized, and the latest farm machinery was on display, including a small Scottish plow and a machine for thrashing grain.

From 1889 to 1918, agricultural fairs were held regularly at the skating pavilion, located near the current cross of sacrifice. The building was constructed in 1889 for the Quebec Skating Club and hosted agricultural shows. It is also where the Société d’horticulture de Québec held its 1897 exhibition. At that time, most exhibitors were Francophone, reflecting the city’s changing population.

Military reviews and manœuvres

In the early 19thcentury, officers garrisoned in Quebec City began organizing military reviews and manœuvres that were true spectacles. Including parades and mock battles, these rather outstanding performances attracted many curious onlookers as well as high-ranking officers, governors general and members of the Royal Family. Guests were received with “impressive decorum and a rigorous protocol.”

At the end of the 1830s, the stormy political climate in Lower Canada drove authorities to display their military force with the goal of intimidating the French Canadians. On June18, 1838, the troops commemorated the victory of Waterloo by holding a great parade on the Plains of Abraham. Also with great pomp on June 28, the garrison celebrated Queen Victoria’s coronation in the presence of Lord Durham, Governor John Colborne and all of the officers. For patriot sympathizers in the region, the message was clear. Indeed, the military garrison’s presence in Quebec City, combined with the Anglophone population’s predominance, greatly dampened the patriot movement’s zeal.

Again at the end of the century, deployments on the Plains were intended to serve national and political rivalries. In 1880, with preparations being made for an imposing Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebration, military authorities organized a parade to honour Queen Victoria’s birthday on May 24. The army and volunteers took the Plains by storm in a grandiose mock battle with the population looking on. This military manoeuvre would “stole a march on the great celebration planned for the following month—a celebration intended to spark the national pride of French Canadians.”

Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day

Some Saint-Jean-Baptiste Days will live on in history because of the scale of their celebrations. Such was the case for the National Convention of 1880, organized by the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Québec. The event assembled French Canadians from across North America, and it was planed so as “to cement the union between French Canadians.” The Plains of Abraham served as the backdrop for celebrating the French Canadian nation. Some 50,000 people attended a pontifical mass on the Buttes-à-Nepveu celebrated by His Eminence Taschereau, the Archbishop of Quebec. The secretary of the National Convention, J.-J.-B. Chouinard, recounted that “the battlefield of the Plains of Abraham shuddered under the feet of a people whose most pure blood it had swallowed one infamous day.” A parade included some twenty floats representing the different social groups. The same evening, a great national banquet at the skating pavilion closed the event, marked by a succession of patriotic speeches tying together allegiance to the British Crown with loyalty to the French Canadian nation. During that banquet, O Canada was sung for the first time in public. Written by Judge Adolphe-Basile Routhier, with music composed by Calixa Lavallée, the piece electrified the audience. In 1980, one hundred years later, the federal government proclaimed it Canada’s national anthem.

Canada Day

Confederation, passed on July 1, 1867, was celebrated in grand style in the city of Québec. Businesses were closed for the day and the entire garrison assembled on the Esplanade. The reading of the royal proclamation inaugurating the Dominion of Canada was punctuated by an artillery salute at the Citadelle. Festivities continued on the Durham Terrace and the morning ended with a rendition of God Save the Queen. In the evening in Québec, lights from houses shined brightly while fireworks capped the festivities. During the following century, regular annual events highlighted the anniversary of the Dominion.

During the commemoration of Canada’s centennial in 1967, the National Battlefields Commission honoured the centennial with the inauguration of the Centennial Foundation near what is now the Edwin-Bélanger Bandstand.

In the 1980s, the federal government contributed financially to the organization of local festivities across Canada. At the time, firework displays were organized in major Canadian cities. In 1982, Dominion Day officially became Canada Day. Almost every year since then, Canada Day celebrations have followed Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, celebrated a week earlier. As always, the grassy expanses of the Plains welcome family activities and the impressive outdoor show that Quebecers so greatly enjoy.

Buffalo Bill – 1897

As of the late 18thcentury, circus acts traveled to the Plains of Abraham site, which was ideal for such events. In 1797 and 1798, Philadelphia’s Rickett’s Equestrian and Comedy circus company gave the first performance on the Plains, with horse shows, dancing, comical songs, exotic animals and fireworks.

The most prestigious circus to perform on the Plains in the 19thcentury was unquestionably that of Colonel William Frederic Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill. A former scout in the American army and buffalo hunter known throughout the American West, the famous cowboy created his own show. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performed the most popular scenes from the American Far West: stagecoach attacks by “redskins,” rodeos, buffalo hunting, etc. Buffalo Bill and his company of over three hundred riders arrived in Quebec City at the end of June 1897 and set up camp on the Plains of Abraham, at the old Quebec Turf Club racetrack, facing the current Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. The company gave four performances to relatively small crowds, as the 50-cent ticket price was obviously discouraging to many.

Charles Lindbergh – 1928

Less than a year after Charles Lindbergh’s famous flight across the Atlantic, the American pilot made a brief stop in Quebec City to help save Floyd Bennett, a fellow pilot who was bedridden at Jeffery Hale Hospital, suffering from pneumonia caught while rescuing German pilots who had made an emergency landing on an island near Labrador. They were completing the first east-west crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. Floyd Bennett was accustomed to the Arctic, having been the first to fly over the North Pole in 1926, together with fellow American Robert Byrd.

On April 24, 1928, Charles Lindbergh took off from New York with a serum aboard to cure Bennett. Lindbergh reached Quebec City in under four hours, landing in Battlefields Park for a hero’s welcome by the crowd. He was also received for dinner by Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau and spent the night at the Château Frontenac. Lindbergh flew back to New York the next morning; at the same time Bennett would pass away.

Charles Lindbergh on the Plains of Abraham in 1928.

Credit: Unknown.

Eucharistic Congress – 1938

Since the 17thcentury, Quebec City has been a major religious centre for North American Catholics, and therefore hosted several major religious gatherings. The Eucharistic Congress of 1938, held in large part on the Plains of Abraham, is one of the most significant.

With its 25,000 religious community members and 4,000 priests, the Catholic Church of Quebec was at that time a dominant force in Quebec society. In the face of modernity however, it began to run out of steam, and so it opted for grand public demonstrations to revive believers’ faith. With this in mind, Cardinal Jean-Marie Rodrigue Villeneuve organized a national congress in Quebec City, giving the population an opportunity to issue a collective profession of faith.

Under the theme of the Eucharist, the National Eucharistic Congress of Quebec was held from June 22 to 26, 1938. All religious movements of the Quebec City Diocese, as well as many others from Canada and the United States, were represented. The event had two components: study sessions and public events. The Cardinal of Quebec City was appointed papal legate for the occasion and, as such, could don pontifical vestments. Cardinal Villeneuve wanted to make Battlefields Park “the Field of Peace of peoples united around the altar, in the most moving communion of faith that we can conceive.” The City was decked in yellow and white, the papal colours. The Congress was visible everywhere, and triumphal arches were built, through which the final procession would go.

The circular bleachers and the temporary altar installed on the Plains of Abraham for the Eucharistic Congress of June, 1938.

Credit: W.B. Edwards, Archives of the National Battlefields Commission.

At midnight on June 23, the Congress opened with a mass around the altar specially built on the Plains of Abraham, with seating for over 100,000 people. During the opening ceremony “some 150 priests gave communion to more than sixty-five thousand of the faithful.” The next day, before a crowd of some 80,000 people, about a hundred young people performed the great drama Le Mystère de la messe. The Congress closed with a grand procession through the City’s streets, starting in front of the Quebec Basilica, descended Côte de la Fabrique, Rue Saint-Jean, Chemin Sainte-Foy, Avenue des Braves, Chemin Saint-Louis, before ending up on the Plains.

Seventy years later, the International Eucharistic Congress will be held in Quebec City from June 15 to 22, 2008, under the theme “The Eucharist, Gift of God for the Life of the World.” The closing mass will also be celebrated on the Plains of Abraham.

Superfrancofête – 1974

The Festival international de la jeunesse francophone, an international Francophone youth festival, was one of the biggest events ever held on the Plains of Abraham. This gathering was aimed at strengthening bonds among Francophones worldwide. Despite the provincial and federal governments’ fears of a nationalist celebration, Quebec City was chosen as the site for this first international edition.

The festival, popularly known as Superfrancofête, took place on the Plains from August 13 to 24, 1974. Some 1,500 artists, athletes and researchers aged 18 to 35 from 25 francophone countries met to share cultures. After a parade and an outdoor supper, the opening show featuring Gilles Vigneault, Félix Leclerc and Robert Charlebois attracted over 125,000 people. Even Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Premier Robert Bourassa attended the event, sitting on the grass surrounded by police officers. The evening closed with the song Quand les hommes vivront d’amour by Raymond Lévesque.

That “Woodstock of Francophone youth,” as it was described at the time, went down in history. The former prison’s outside yard was transformed into an arts village boasting a hundred or so craftspeople from around the world. This gave visitors an opportunity to discover a wide array of foreign handicrafts, and helped craftspeople forge ties with their international counterparts. Performances by Francophone artists livened up the festival, which welcomed over a million visitors, raising awareness of belonging to the international Francophone community.

Chant’Août – 1975

The year after the successful 1974 Superfrancofête, Quebec’s Ministère des Affaires culturelles organized a festival to boost the development of song writing in Quebec. The Plains once again proved to be the preferred location for the event called Chant’Août. From August 10 to 17 over 500 artists, including almost all the big names, gave concerts attracting close to 100,000 people.

Quebec City’s tricentennial celebrations – 1908

In 1908, Quebec City’s tricentennial was marked by elaborate celebrations, where various dignitaries were received, including the Prince of Wales, who would go on to become George V, as well as C. W. Fairbanks, the American Vice-President. They were joined by several Canadian statesmen, including the Premier of Ontario, as well as delegates from France and British colonies. A fleet of battleships fell into line on the seaway below, while over 12,000 militiamen and 3,000 seamen paraded along the City’s streets.

The most outstanding event proved to be a grand historical performance assembling over 4,000 extras and actors on the Plains of Abraham. Great historical moments conveying specific messages were played out, as described by the historian H.V.Nelles in the following:

[…] that French Canada too had noble origins; that French possession and occupation of New France was just; that civilization had always been a joint responsibility of church and state; that as a people they had survived many trials through faith, strength of character, and boldness; that they had not been conquered; and finally that their loyalty to Britain had been proven in battle.

The idea behind the tricentennial festivities was to present Quebec City as the “cradle” of Canada. There was a desire to make the event an assembling celebration, especially to bring French and English Canadians closer together. Incidentally, with this in mind the Prime Minister of Canada, Wilfrid Laurier, agreed to establish the National Battlefields Commission, responsible not only for supervising the organization of celebrations, but also for acquiring and developing the grounds required for the creation of Battlefields Park. It was to become “the shrine of union and peace […] where two contending races won equal and imperishable glory.”

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800–1900”, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 146.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800–1900”, p. 147.

John Hare, Marc Lafrance, David-Thierry Ruddel. Histoire de la ville de Québec, 1608-1871. Montreal: Boréal/Musée de la civilisation, 1987, pp. 240-241.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800–1900”, p. 149.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800–1900”, p. 145.

“Buffalo Bill sur les plaines d’Abraham,” Cap-aux-Diamants, vol. 5, no 4, (Winter 1990): 69.

“Lindbergh accomplit un nouvel exploit en arrivant à Québec hier avec du sérum pour Bennett.” L’Action catholique, April 25, 1928, p. 12.

Quoted in Jean Provencher, “A Gathering Place”, in Jacques Mathieu and Eugen Kedl, eds., The Plains of Abraham: The Search for the Ideal, Sillery: Septentrion, 1993, p. 279.

Jean Provencher,“A Gathering Plac,”, p. 280.

Quoted in Jean Provencher, p. 283.

H.V. Nelles," The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary", Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999, pp. 182–3.

H.V. Nelles, " The Art of Nation-Building: Pageantry and Spectacle at Quebec’s Tercentenary", p. 38.

Quoted in Donald Guay, p. 149.

Donald Guay, “Sports, Culture and Leisure, 1800–1900”, p. 150.